I’m careful to make sure that no one in the apartment building next door observes me. A few weeks earlier residents of the apartment building exchanged gunfire with a passing car. The bullets shattered several windows and the front door of the building. I pick up the key hidden below the dangerous dog sign on the front porch where my friend told me I’d find it. She left South Minneapolis on short notice to go to the East Coast to visit family and asked me to look after her dog.

The old Victorian house is quiet and still when I enter through a side door. In the living room, couch cushions puff out air followed by the click-click-click of toenails across the hardwood floor. The coo of doves fills the living room. Metallic slurping comes from the kitchen.

The 85-pound, thirteen-year-old pit bull/boxer, looks up at me with his broad tan face. Two vertical furrows form between his droopy eyes. His gray muzzle opens slowly, and he lets out a throaty bark. I run my hand down the back of his head. ‘You were never dangerous,’ I say to his imploring face. He lets out two short, sharp barks. I pat his muscular shoulders. Inside the refrigerator I find an array of ceramic bowls with meals handmade by his master.

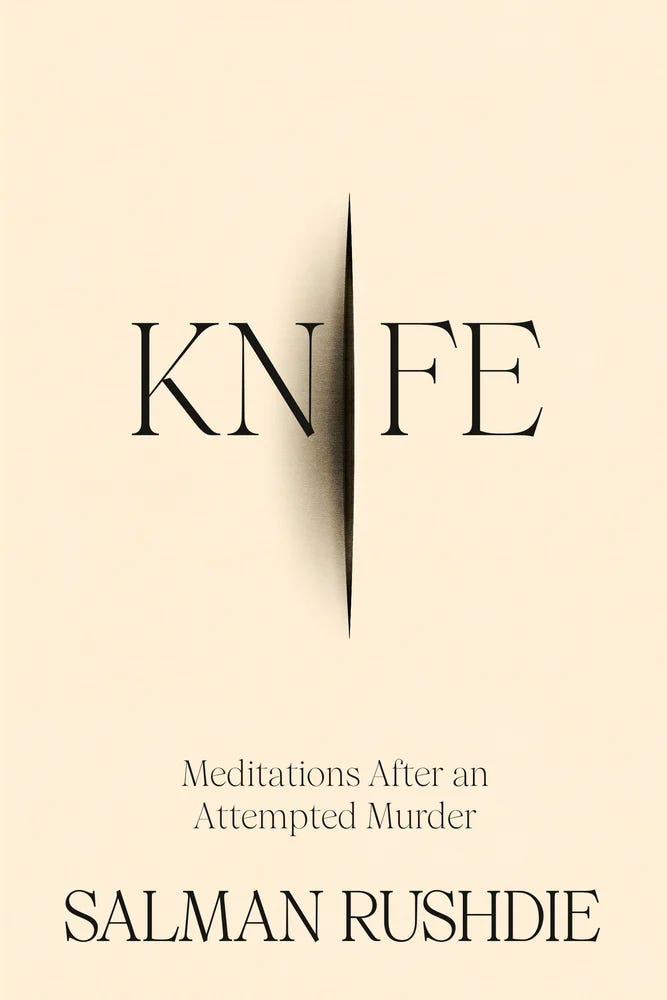

I put a bowl of food on the floor next to the kitchen Island. While the dog gobbles down the food, pushing the bowl across the floor, I pick up Knife by Salman Rushdie off a table laden with books. The doves flap their wings, bow coo, and crunch the litter in the bottom of their cages. A man charges the Chautauqua stage toward the standing Rushdie. The empty food bowl thuds against a side table. I ignore the sound and follow the charging man with the knife. Audience members come to Rushdie’s aid and tear off his brand-new Ralph Lauren suit to assess his wounds. The dog continues to lick the bowl, polishing the surface until it gleams.

I abandon the wounded Rushdie sprawled out on the stage, and say to the dog, ‘Ready to go out?’

I open the back door. A rush of fresh air flows into the house. The dog lumbers out onto the stage-like deck, stumbles down the three shallow steps and disappears into a thicket of trees so dense that I can’t see the back-alley garage thirty feet away. The screen door slams shut behind me. For a moment I see the world-renowned author in a pool of blood on the deck before me. Phantom gunshots and shattering glass come from next door. Not far away the outline of George Floyd marks the painted pavement. I follow the dog down the steps onto a cobblestone path, a remnant of when landscaped order prevailed within the seven-foot-high wood fence which encloses the quarter acre backyard.

Shortly before the pandemic, my friend decided to let her backyard go wild. No mowing, no pruning, no weed whacking, nothing. In that time maple trees took root, pine trees sprouted up, nettles burst forth, and all manner of vines curled around the trellis and trees. Cardinals, nut hatches, gold finches, robins, rabbits, rats and snakes all moved in. Milkweed blooms in one area with a small population of butterflies. Hummingbirds flit from yellow and purple wild prairie flowers.

On this July morning speckles of sunshine penetrate the canopy of the little forest. The dog rustles the undergrowth as he looks for a place to do his business. A rabbit hops by from the bushes in a dash to safety under the deck. I forget about the wounded Rushdie, the gun shots, and the paint-covered pavement. They fade into an invisible pressure against the tall fence. Wind hisses through the pine boughs. In the crook of a swaying pine branch a mamma and papa cardinal take turns feeding a fledgling. The overgrown cobblestones remind me of the ancient roads of northern France. I take the shovel leaned up against the garage and clean-up after the dog.

It's satisfying to see the dog joyfully romp in the undergrowth after relieving himself. I think of my friend visiting her family, happy to see them for the first time since the pandemic began. Back in my own life there’s household chores to do, final changes to a novel to review, and preparation for a trip to the West Coast. It’s the first time I’ve felt possibility, useful, and truly light since an emotionally dark fall and winter.

The dog bursts out of the trees, his hind legs moving with a hitch. He stops at the bottom step of the deck. He looks at me again with the imploring eyes. I take his hindquarters in my hands and help him up the steps. On the deck he turns toward the little forest to survey his domain. He barks his throaty bark.

Back inside I resume reading Knife until Rushdie is recovering in the hospital. The dog slurps down some water and hops up on the couch. I leave the house by the side door and return to the front porch. I’m careful to make sure that no one in the apartment building next door observes me when I place the key below the dangerous dog sign. The outside world presses in, but I feel the strength to push back.

Thanks, Christopher. I enjoyed this one.